I have suggested in previous postings that the attempt to take language and

conceptualisation from a traditionalist culture (such as South Asian)

into a modernised and modernising one was more likely to obfuscate than

enlighten. On the other hand, I suggested that traditionalist cultures

had a great deal of a practical nature to teach us about techniques for

personal development.

The problem here is that the West’s tendency is either to dismiss

non-Western thinking entirely as non-scientific, or even dangerous if

mishandled, or to turn it into a fetish by adopting the forms of a

tradition but not investigate the deep meaning of the thinking involved with a

philosophical eye.

The classic case study is Neo-Tantra where the use of sexual

activity for personal transformation on an occasional and highly

disciplined basis linked to a very traditionalist vision of society has

been transformed into a sort of couple guidance therapy for confused

liberal adults. These ‘followers’ persist in using Sanskrit names, about which most

must have limited understanding, to act as cover and excuse for

something for which there should be no cover or excuse at all – good sex

between willing adults.

The sacralisation of sexuality is getting out of hand. One of the

reasons for this is that sexually healthy Westerners, especially women,

constantly have to make excuses in our prevailing culture for having a

perfectly healthy or business-like attitude to what is often a risky

(though less so today than at any time in history) but otherwise highly

pleasurable, amusing and very creative activity.

Having to engage in personal relations with a ‘blessed be’ or a

‘namaste’ in tow is a back-handed compliment to the dominant repressive

culture. It takes open attitudes to the body and sexuality (and to

transgression that harms no one) and puts them into a box that contains

the libido as far away from the ‘normal’ world as is possible in a free

society.

This containment process uses ritual and strange language forms in

order to make a high price of entry to anyone who wants to express

themselves openly but without the ritual baggage. It is self censorship

with sacral sub-cultures doing the system's work for it. ‘Conventional’ culture, outside these ‘sacred’ models to which we

might add Thelema and many others, then throws healthy sexuality into

two challenging pots – the ‘normal’ which avoids the subject altogether

and ‘swinger’ or ‘fetish’ sub-cultures where identity is sexual and

little more. True sexual normality is avoided in every way possible –

conventional, sacral or sub-cultural.

Those who lose themselves in ritualised separation are not to be

condemned or blamed for this at all. As we have seen from the sheer

effort required to expose something that was an ‘absolute wrong’

yet protected by conventional attitudes to the inconvenient truth (priestly

child abuse), those with a radical or free sexuality, having seen

previous waves of liberation crushed by material reality and cultural

conformity, have every reason to create closed self-protective

societies.

In this, they are like early Reformation reformers faced with the

sheer weight of Catholic cultural power. The excessive sacralisation of

sexuality in mock-traditional clothing liberates in one direction only

to create psychological bondage in another.

The Early Reformation analogy is a good one. The Reformers rebelled

against the Church but only within some of the same assumptions about

the existence of God on peculiarly Christian magical lines and men were

killed over transubstantiation in a way that now seems absurd. A genuine revolution against deist obscurantism only seriously took

hold in the eighteenth century and saw equal status for conventional

God-worshippers and more relaxed and indifferent others (and then only

in the most advanced communities in the world which still do not include those

of the American backwoods) in the last fifty or so years.

You still do not get much a choice in the matter across the bulk of

the Islamic world or, if you accept communism as a world religion, where

Communists rule.

Our current revolution in sexuality is still operating on

Judaeo-Christian assumptions redrafted in the forms of nature religion

and traditionalism. It has still to break free and become a

non-essentialist and humanist response to the scientific understanding

of the merging of brain and body.

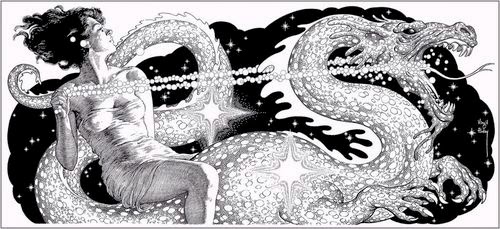

Let us concentrate on just one concept that has migrated from the

East to the West – Kundalini, the coiled bodily energy allegedly

positioned at the base of the spine that is analogous to the source of

libido in the West, unconscious and instinctive.

This energy, which some of us feel more than others, was placed in

the Western brain by scientists at the beginning of the last century but is now seen

to be as much operative in the flow of chemicals throughout the body as

in some free-floating unconscious.

The South Asians literally embodied this force, with great

imagination, as a snake or as a goddess. The force is Shakti and it

comes into play when Shiva and her consort make love. We (as humans)

repeat with appropriate reverence this divine coupling when we make

love. It is an approach to 'spiritual experience' deliberately abandoned by the

Christian priesthood.

But this is not going to be a polemic against the New Age appropriation

of the idea of Kundalini or against the simplicities of Neo-Tantra. On

the contrary, the arrival of every new idea has to be seen in its

context – what purpose did it serve that made it attractive? The arrival of bastardised forms of South Asian thinking have proved

a powerful liberating half-way house between a previous state – in

which Judaeo-Christian mentality wholly disembodied libido – and a

future state in which (thanks more to the slow process of scientific

discovery than revelation) libido and embodiment require no special

rationale but are seen as two sides of the same coin of simple human

‘being’.

One of the great questions here, because Kundalini is described in

goddess and snake terms, is whether art or imagination hinders or helps

true understanding.

I would contend that, where there is no materialist or scientific

language for what we ‘know’ from introspection or experience (but which a

whole culture insists on denying), art and imagination have to come

into force to avoid total dessication of the soul.

But sometimes art or imagination can become neurotic, obfuscate and

cause us to avoid the truths that scientific investigation reveals. So

it is with sexuality and Kundalini. The reality of Kundalini is ignored

in one culture (the West) but then turned into a goddess or sleeping

serpent in the other (the East).

The latter is an improvement on the former but it is not ‘truth’ and

it gives excessive power to priests and gurus and teachers who

allegedly interpret the signs and symbols of the practice. The point

being that the central lesson of Kundalini thinking is that it must

be a release from signs and symbols.

In a traditional society, the language of signs and symbols are less

easy to escape than in a modern society precisely because we have so

many of them.

We have so much choice that we can be cavalier about their

importance and being cavalier about signs and symbols is the first step

towards rejecting them to ‘find oneself’. Simply replacing one set of

signs and symbols with another – as in Neo-Tantra – misses the point.

The truths in Kundalini are perhaps best understood in terms of

‘visualisation’ – the ability to master the body through the systematic

use of imagination (which involves focusing down on signs and symbols in

order to eliminate them) is analogous to the rational mental modelling

used to master one’s immediate social environment.

The self and society are interlocked through body. The body encases

the physical systems that underpin the emotion and instincts that

interpret perception and make the paradigms of thought. The body is also

the tool by which the mind communicates both directly and through social

signs to others.

The body, in short, is central to the flow from mind to society and

from society to mind. Social control of the body is a means of

controlling the mind and mental command of the body liberates one from

enslavement to others.

Disembodied mind (especially when infected by pure reason) is

useless in managing society effectively. The body in its animal state

cannot have any form of meaningful consciousness, let alone a

‘spiritual’ one.

The coil that is Kundalini sits at the core of the sacrum bone.

This, in itself, is significant. It is where our ‘gut’ meets the ground

when we sit, rested. Our feet connect to the ground, of course, but our

feet connect in action and action is our working on the world, our

social self.

When we think we sit - just as we lie down to sleep and lose

ourselves in our unconscious dreams at the other end of the awareness

spectrum. Sitting places the base of the spine close to the ground.

In the visualisation, we uncoil ourselves from our base in matter,

not accidentally closest to the point where we exude matter in

defecation, in a series of stages up to the highest experience of being

within the mind itself.

The process of unravelling self from ground to mind can presuppose

what that ground is (all matter is much the same at core) but cannot

presuppose how the expression of self will develop though to the final

state of alleged ‘pure consciousness’ which seems also to be much the

same at core whoever experiences it.

The variability of imaginative meanings for Kundalini matches the

variability in selves so that the libidinous truly represents only one

type of mind that is of equal value to the mind whose highest method is

thinking and another whose method already implies the sense of being

‘at one’ with all things as pure consciousness from the beginning.

The common denominator is that the highest state of possible being

is one where a person recognises themselves as integrated with matter as

matter-consciousness even if some are deluded into thinking that they

have become pure consciousness (as if the mind can ever actually detach

itself from the body).

Does pineal gland activation have some link to the

sense of heightened awareness associated with reality (confirming an intuition of Descartes)? The research is unclear but the scientific exploration of

‘spiritual states’ is still in its infancy - some of it indicates that

“the practice of meditation activates neural structures involved in

attention and control of the autonomic nervous system.” The physiological basis of spiritual states seems increasingly

likely to be demonstrated as biochemically connected without in the least diminishing the

importance and value of those states.

The self-awareness of matter-consciousness arises ultimately and

only from the manipulation of matter in stages - not always through

conscious mastery of the body but also (as in the tantric or shamanistic

approaches) through the employment of different aspects of the body,

moving stage by stage until that aspect of the body that is

mind-without-social-signs-and-symbols can come into play. A combination of visualisation and the awareness of the different

aspects of the body can become the means to experience the body-mind as far from

its social creation as is possible. The mind is not detached from

matter at all but only from the signification of the social which is

presumed to be matter because it is based on matter (which is not quite the same

thing).

Indeed, against all doctrine, it might be said that the final stage of awareness

is as much pure matter as pure consciousness. It is not a stance that we can hold for long without a large

peasantry servicing our needs or a very modern leisure economy – there

were good socio-economic reasons for the turning away from sacral ideas in modernity: they become inutile, unnecessary.

The full range of techniques to be desacralised are varied – meditation, breath control, physical movement, chanting. I

have privileged visualisation only because this is the technique that is

most conscious of the breadth of symbols that surround us and which

will detach us from our own matter-mind best, not by isolating the brain into

one set of symbols (such as sound or patterned image) but by developing a

narrative of symbols that shift and change to reduce phenomenal noise.

All techniques may have the ultimate effect of detaching us from a

world made up of signs and symbols and attuning us with our own inner

matter as refined ‘consciousness’. Both alchemical analogies of moving

from base lead to gold and various Gnostic formulations spring to mind.

The difficulty lies when we detach a convenient tradition from the

scientific basis to the process. The ‘shaktipat’ (blessing) of the

Siddha-Guru may be regarded as a signal of permission to begin but there

is no reason why, after a commitment arising from oneself, one might

not bless oneself, give oneself permission, if you like, to exist.

Injunctions on purification and strengthening of the body might

equally be seen as a discipline of detachment – a removal of

distractions in order to concentrate on the job at hand and it should

need no funny little rituals if the mind is aligned properly.

The aim is to ‘sense’ the energy move from sacral bone to crown of

the head and the metaphor of unification of the goddess with the Lord

Shiva of Creation is only a metaphor of apparent unity of personal

matter-consciousness. The profound illusion that the mind is one with the greater

matter-consciousness of the Absolute is a physiological one but the

illusion does not matter. The transformative power of the experience is

what matters.

Far from not being a physical matter (as Eastern adepts insist), the

final moment is the ultimate physical occurrence where we use

‘consciousness’ to describe only a state of a matter that we have not

described before.

It is not the world that is the illusion (except insofar as the

signs and symbols of social intercourse are an illusory shell over very

real matter) but our own pretensions. In gnosis, our mind is physically

enabled to see things and to make connections that mere rational thought

does not permit.

If this is gnosis’, it is gnosis of a higher state of matter that

embodies a consciousness of a more sophisticated nature, detached from

phenomenal distractions. The state of being that arises – repeated in

its attributes amongst people from many different cultures – is ‘gnosis’

of oneself and one’s place in the world and it tells us nothing about

an Absolute which remains unknowable.

To experience this state of being and to allow oneself to wallow in

its illusion is to misuse the experience. Its purpose is to re-ground us

in the world, giving us a more critical understanding of the reality of

the world that has been presented to us as real but is actually based on

perceptions of underlying reality that are so often given to us rather

than chosen by us.

Similarly, despite the fears of ‘experts’ at the dangers of this

sort of thinking, it is wonderfully democratic in its potential – once

the priests and gurus have been put in their feudal place, modern man

can make eclectic use of these techniques and others to develop a

critical stance to authority and the ‘given’ without becoming lawless.

The energy derived is natural (in the original culture, Shakti is

also Prakriti which is associated with the idea of nature) and as much a

part of the world of science as the building of an aeroplane. The base

of the experience is the formlessness of all of our past, including

forgotten things that make our habits what they are.

The start of the visualisation process requires an engagement with

the fact of the unconscious, the deep well of rubbish that is ourselves

as constructed by others. From that simple truth, the serpent uncoils,

forcing its away up - unless impeded by a fearful conscious will.

Even amongst the scientific papers, you can sometimes sense the fear

of the rational mind at what this thinking might do to their world of

signs and symbols.

The principle is also feminine for only accidental cultural reasons. It

is a principle in defiance of order and the order of society is

presented as a male principle. It suits the male who is an adept to see

the principle as operating against his given nature which is male and it

is no accident that the final stage has the principle of the feminine

uncoiling and then bumping against a masculinised Absolute.

This, in itself, should make us cautious about the tradition as it

is promoted in the West because the energy does have libidinous and

erotic aspects and does involve coupling of sorts and yet it might be

considered in other ways by other minds. The sexuality involved though is

'normal' - a means to an outcome.

Nor is there anything inevitable in nature about the process. The

normal mode of being in the world is actually to avoid questioning and

to embed one’s self in given signs and symbols.

Only a few people, often because of an edgy dissatisfaction about

the given world, feel obliged to start a search for ‘meaning’ (in itself

a futile search except in the performing). It requires much hard work

and some risk in terms of social benefits to pursue something that may

be a necessity for some (and so ‘natural’) but by no means for all.

There are no intrinsic impulses in nature, only in some persons.

The particular association of the sexual and spiritual, for example, is a private

one (even when such practices involve groups engaged in experimentation) but all

methods have in common a sense of increasing internal unification based

on a ‘working’ of the libido and the body. Jung seems to have grasped

this better than most in seeing the process as one, essentially, of

individuation.

Showing posts with label Mind. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Mind. Show all posts

Saturday 20 June 2015

Friday 29 May 2015

Reflections on Personal Identity

The common Western idea of personal identity has depended on continuity of

memory since John Locke and is a central element in English

individualism.

This was contrasted with ‘mere’ bodily continuity, with mind and body

firmly separated, which was assisted by another notion – that mind was associated

with a ‘soul’ which had some being or continuity beyond the body after

it had died (or even outside the body, while the latter was still functioning separately, in some

schools of thought).

This idea of a continuity beyond death, based on a separation of body and mind, is still held by many people as a matter of faith. It gives psychological comfort to some but it has not been demonstrated as ‘true’ (scientifically probable). It is a possibilian concept. Continuity of memory, however, is a different kettle of fish. Since Locke’s day, we have seen ‘scientific’, certainly suggestive theoretical, evidence that conscious memory, accumulated in layers of perception and constantly constructing the ‘self’, is only a small part of the story.

We have Freud’s postulate of the unconscious to contend with but also growing evidence that the historic genetically constructed structures of the brain construct both our perceptions and the selection and holding of those perceptions in such a way that memory becomes a very slippery matter in its relation to what actually happened even in the moments before it is formed. Memory is not just the accumulation of perceptions into a form of identity but the unwitting selection of perceptions, one that relies on discontinuities, redrafts and revisions that are built-in to the ‘person’ by their genetic and experiential history.

There may be an inability to perceive some things or a determination to forget in the context of trauma or some other need. If personal identity is memory then that personal identity is not smoothly constructed in many cases but is a partly wilful and partly unconscious creation which involves as much forgetting as remembering. This is not incompatible with, say, the metaphysics of Nietzsche to the effect that we can be nothing other than we are and that we are doomed to repeat ourselves eternally.

The ‘will to power’ (in his sense) of an organism that integrates body and mind into a being that is also integrated into raw existence can easily accommodate the idea that we are not conscious of the discontinuities as well as conscious of the apparent continuities in our identity. Indeed, the mix of conscious and wilful (or apparently so) change in ourselves with part-conscious (or illusory) and with unconscious (or biological or environmental) changes to the forms by which our perception is structured is in greater accord with Nietzsche’s existentialism than with Locke’s gentlemanly English liberalism.

Modern psychologists are only the professional end of a truth universally recognised by most of us who can see the world in a critical way – that memory is as often false as not and so, by extension, that our personal identities are ‘false’ constructions that: a) depend on our body’s and earlier mind’s determination of what should be perceived and then held for future use; and b) are what that same mind should unconsciously choose to forget or bury deep in the process of creating the present which we can then call our ‘self’ at any one time.

Memory, in short, is not all that personal identity is but is only its expression to our consciousness. Placing the possibility of existence beyond the body to one side, our personal identity may be a memory at each point in our life but that memory is possibly false and our personal identity is probably false if we believe it to be true without further questioning. By a paradox, if we know and believe our memory and identity to be ‘false’, it becomes more ‘true’ (yes, truth can be relative here) because the entry of the thought of a false memory as possibility, even probability under certain conditions, gives us the opportunity to choose to be ‘critical’, that is either to accept our personal identity as ‘true’ for us in its falsity as an act of will and freedom (insofar as we can ever be free) or to investigate, critically, what may be false in order to make ourselves more ‘true’.

We are not valuing the ‘true’ here as the ‘good’ – being ‘true’ is merely defined as according with objective or at least scientifically validated reality. Being in accord with objective reality has no necessary relationship in itself with the value of ‘good’ but that is another debate. Personal identity, in fact, is never anything other than ‘true’ in value terms because it is ‘true’ to the person that has that identity. The ‘falsity’ arises only when the person perceives a ‘falsity’ themselves in what they had held to be true, hence the argument in this note – that realisation of ‘falsity’ requires a new ‘truth’ or new identity formulation even if this is a reaffirmation of the ‘falsity’ as ‘truth’. In this way, once we understand that Locke’s assertion that personal identity is memory is to be taken as a truism of sorts, but one without much relationship to the objective truth of our condition in the world – that is, that ‘false memory’ means ‘false identity’ in any terms that are not totally subjective to the person and so represents more or less of a disconnect between persons and their world – then we can rethink that position in the world

This must generally result in one of three responses – denial, conscious reaffirmation of the given or critical investigation of the self. Let us pause here and say that no value judgement can be ascribed to any of these responses. The denial that a person is anything other than memory, even if the memory (say) includes the assertion that the person was once Emperor of France when all the external evidence points to this not being case, is a legitimate human response to their condition in the world.

The assertion that the historic world leader and this person who believes themselves to be (wrongly) that past world leader are different in personal identity terms just because one accords with objective reality and one does not is merely a matter of the degree by which the identity is practically adaptive to the world. All those unaware of their ‘falsity’ have more in common, mad or not, than any of them do with those who are aware of it. Madness and 'inauthenticity' (to use an older and rather value-ridden existentialist term) are far from identical however. 'Inauthenticity' may be a necessary condition for personal survival in the world as it is constructed. Madness is a poor way of physically surviving in the world outside the most caring of welfare states, communities, tribes or families.

Each personal identity in its particular case of unawareness has been constructed to function for that person but both cases, madness and 'inauthenticity', have in common the fact that neither is aware of their condition or, until having become or made aware of it, are able to treat that condition critically. The thought experiment here is of the man who chooses madness in response to conditions and becomes mad - is this possible? Did Nietzsche do this? Was this his genius? Human society, on the other hand, could probably not function easily without the vast majority of persons not questioning their condition for most of the time. Unquestioning is a necessary element in the construction of the social.

Left critics of the workings of society have been fully aware of this for some time, hence their frustrated assertion of the need to act to raise consciousness in order to effect change because, left to themselves, most people would accept existing conditions as true and construct their personal identities precisely to fit their environment. These people become their world – cogs perhaps but also able to survive where those who question might end up in camps or penury. It is the source of the instinctive conservatism of the mass of the population and the difficulty behind attempts to effect change even when all logic points to it.

But being or becoming aware of the fact that our personal identities are ‘false’ to the degree that our memories are false because we are our memories (albeit embedded first in a body with its memory and a society with its collective memory) creates only persons who are different not better and the uncovering of this truth about identity does not necessarily result in more than marginal change. The conservatism of society is often very logical – just as are the narratives of the great movements that challenge this conservatism.

Our bodies, meanwhile, are repositories of unconscious material memory. Their genetic component (without going down the route of the collective unconscious) means that a proportion of that memory exists from before the actual creation of that body. Societies too are repositories of collective memory. The habits and instincts of persons are easy to transfer from one community to another (certainly under conditions of modernisation) but also respond (without further self-questioning thought) to the ‘norms’ of a particular time and place which then impact on the formation of memory and so identity. Memory is constructed out of continuous socialisation and the relationship between memory and social identity is at the heart of 'tradition'.

To challenge one’s own personal identity may often involve challenging one’s own body image and capabilities, the ‘norms’ of society and the representation of oneself in society – it might even suggest radical action: gender change, migration, abandonment of tribe or faith (or acquisition of one). The point is that knowing that one’s personal identity as a construct of false memory does not necessarily predispose someone to radical rather than conservative actions.

It enables radical choice, that is true, but radical choices, if based on unconscious reaction to the tension between society and material circumstances and ‘true will’ can be far from conscious. They may derive from a reaction to memory that makes them no more authentic than those of the conservative mind set who determines on full acceptance of his or her condition without further thought. Awareness that memory and so identity can be explored and reconfigured is a-political and even a-social.

The only virtue of awareness is that it does not rely on an unconscious balancing of mind, body and society (which clearly creates contentment for some but not others) but recognises that, where the mind is not in accord with body or society and where personal identity is not in line with something approaching ‘true will’, the person, in that moment of recognition, can make choices and that those choices involve the management of perceptions and the investigation of memory (or the abandonment of acceptance of memories as valid in the rejection of beliefs) in order to realign a person and the conditions of their existence.

In the case of beliefs, memory is certainly slippery. To believe something is a core element in personal identity and the shift of a belief from a present state to a memory of what was once believed represents a major shift of identity in itself. Chaos Magicians exploit this in order to play with their own identities in a way that strikes the vast majority of humanity as wasteful and absurd but these are not idle thought experiments in coming to a view on the stability of identity in our species.

So Locke is, of course, correct that our identity does rely on memory but we must recognise now that memory is constructed and false more often than not so that our personal identities are as much constructs of our bodies and society as of our conscious will and actual experience. Although this is true, this is not an excuse for a valuation of some minds as better than others just because of their awareness of this falseness of identity because no identity can ever be anything but false in an absolute sense. Nor can we necessarily draw the extreme conclusion that we have no selves (which is an entirely different argument, if currently fashionable one, to criticise another day).

Having an identity that is true to itself is still having an identity that is constructed or that has been constructed out of perceptions that can never tell the whole story about external reality (not to mention our ignorance of other minds and the workings of a society where so little can be observed directly by the subject). An identity expresses the needs at any one time of a person who is made up of a mind set in a body constrained by social and technological reality. Thus, there is never any absolute freedom but nor is there any requirement for total determination of circumstances.

Liberation is merely a cast of mind, a calibration of society, body and mind and so a calibration of perception, of memory and of identity. The constant struggle between the psychological and physical continuity theories of identity thus rather misses the point. What might be better considered is a theory of constant discontinuities in which a body (and a society) and a mind with only apparent continuity are both required but in which the ‘normal’ integration of the two can be discontinued without either mind or body ceasing to have some ‘memory’ of itself.

A body without a mind is still the body of the person and can be reactivated as such under certain conditions (as after a coma) and that body would influence a new mind that entered it through its biology and brain structure. Perceptions and capabilities would change identity – we only have to consider the male/female difference and the effects on a mind with memories of another gender in a body swap to know how identity would adjust with biology. Continuity perhaps but also a recasting of memory to fit biology would be likely.

A mind might be reloaded or transferred or duplicated in a machine or another body but, from that point, the new material conditions would create new ways of perceiving and thought that would create a separate identity from any identical mental clone in another body, whilst still showing continuities with the past through inherited shared memory. In the memory clone case, each ‘person’ has a separate identity based on possibly small changes in material circumstance despite shared memories – reproducing the ‘I’m Sharon but a different Sharon’ problem of Battlestar Galactica.

Identity is not fixed but changes and shifts in relation to the environment. It is fraught with discontinuities even when simplified down to one mind in one body. The recognition of this complexity should make the psychological-physical debate redundant. It should also help us to be suspicious of the truth-claims made about ourselves by ourselves and by all other persons of themselves and create a scepticism about claims that any single mind can have the answer to any social problem without the help of other minds or that any person can have the ultimate solution, if there is one, to one’s own problems except oneself.

This idea of a continuity beyond death, based on a separation of body and mind, is still held by many people as a matter of faith. It gives psychological comfort to some but it has not been demonstrated as ‘true’ (scientifically probable). It is a possibilian concept. Continuity of memory, however, is a different kettle of fish. Since Locke’s day, we have seen ‘scientific’, certainly suggestive theoretical, evidence that conscious memory, accumulated in layers of perception and constantly constructing the ‘self’, is only a small part of the story.

We have Freud’s postulate of the unconscious to contend with but also growing evidence that the historic genetically constructed structures of the brain construct both our perceptions and the selection and holding of those perceptions in such a way that memory becomes a very slippery matter in its relation to what actually happened even in the moments before it is formed. Memory is not just the accumulation of perceptions into a form of identity but the unwitting selection of perceptions, one that relies on discontinuities, redrafts and revisions that are built-in to the ‘person’ by their genetic and experiential history.

There may be an inability to perceive some things or a determination to forget in the context of trauma or some other need. If personal identity is memory then that personal identity is not smoothly constructed in many cases but is a partly wilful and partly unconscious creation which involves as much forgetting as remembering. This is not incompatible with, say, the metaphysics of Nietzsche to the effect that we can be nothing other than we are and that we are doomed to repeat ourselves eternally.

The ‘will to power’ (in his sense) of an organism that integrates body and mind into a being that is also integrated into raw existence can easily accommodate the idea that we are not conscious of the discontinuities as well as conscious of the apparent continuities in our identity. Indeed, the mix of conscious and wilful (or apparently so) change in ourselves with part-conscious (or illusory) and with unconscious (or biological or environmental) changes to the forms by which our perception is structured is in greater accord with Nietzsche’s existentialism than with Locke’s gentlemanly English liberalism.

Modern psychologists are only the professional end of a truth universally recognised by most of us who can see the world in a critical way – that memory is as often false as not and so, by extension, that our personal identities are ‘false’ constructions that: a) depend on our body’s and earlier mind’s determination of what should be perceived and then held for future use; and b) are what that same mind should unconsciously choose to forget or bury deep in the process of creating the present which we can then call our ‘self’ at any one time.

Memory, in short, is not all that personal identity is but is only its expression to our consciousness. Placing the possibility of existence beyond the body to one side, our personal identity may be a memory at each point in our life but that memory is possibly false and our personal identity is probably false if we believe it to be true without further questioning. By a paradox, if we know and believe our memory and identity to be ‘false’, it becomes more ‘true’ (yes, truth can be relative here) because the entry of the thought of a false memory as possibility, even probability under certain conditions, gives us the opportunity to choose to be ‘critical’, that is either to accept our personal identity as ‘true’ for us in its falsity as an act of will and freedom (insofar as we can ever be free) or to investigate, critically, what may be false in order to make ourselves more ‘true’.

We are not valuing the ‘true’ here as the ‘good’ – being ‘true’ is merely defined as according with objective or at least scientifically validated reality. Being in accord with objective reality has no necessary relationship in itself with the value of ‘good’ but that is another debate. Personal identity, in fact, is never anything other than ‘true’ in value terms because it is ‘true’ to the person that has that identity. The ‘falsity’ arises only when the person perceives a ‘falsity’ themselves in what they had held to be true, hence the argument in this note – that realisation of ‘falsity’ requires a new ‘truth’ or new identity formulation even if this is a reaffirmation of the ‘falsity’ as ‘truth’. In this way, once we understand that Locke’s assertion that personal identity is memory is to be taken as a truism of sorts, but one without much relationship to the objective truth of our condition in the world – that is, that ‘false memory’ means ‘false identity’ in any terms that are not totally subjective to the person and so represents more or less of a disconnect between persons and their world – then we can rethink that position in the world

This must generally result in one of three responses – denial, conscious reaffirmation of the given or critical investigation of the self. Let us pause here and say that no value judgement can be ascribed to any of these responses. The denial that a person is anything other than memory, even if the memory (say) includes the assertion that the person was once Emperor of France when all the external evidence points to this not being case, is a legitimate human response to their condition in the world.

The assertion that the historic world leader and this person who believes themselves to be (wrongly) that past world leader are different in personal identity terms just because one accords with objective reality and one does not is merely a matter of the degree by which the identity is practically adaptive to the world. All those unaware of their ‘falsity’ have more in common, mad or not, than any of them do with those who are aware of it. Madness and 'inauthenticity' (to use an older and rather value-ridden existentialist term) are far from identical however. 'Inauthenticity' may be a necessary condition for personal survival in the world as it is constructed. Madness is a poor way of physically surviving in the world outside the most caring of welfare states, communities, tribes or families.

Each personal identity in its particular case of unawareness has been constructed to function for that person but both cases, madness and 'inauthenticity', have in common the fact that neither is aware of their condition or, until having become or made aware of it, are able to treat that condition critically. The thought experiment here is of the man who chooses madness in response to conditions and becomes mad - is this possible? Did Nietzsche do this? Was this his genius? Human society, on the other hand, could probably not function easily without the vast majority of persons not questioning their condition for most of the time. Unquestioning is a necessary element in the construction of the social.

Left critics of the workings of society have been fully aware of this for some time, hence their frustrated assertion of the need to act to raise consciousness in order to effect change because, left to themselves, most people would accept existing conditions as true and construct their personal identities precisely to fit their environment. These people become their world – cogs perhaps but also able to survive where those who question might end up in camps or penury. It is the source of the instinctive conservatism of the mass of the population and the difficulty behind attempts to effect change even when all logic points to it.

But being or becoming aware of the fact that our personal identities are ‘false’ to the degree that our memories are false because we are our memories (albeit embedded first in a body with its memory and a society with its collective memory) creates only persons who are different not better and the uncovering of this truth about identity does not necessarily result in more than marginal change. The conservatism of society is often very logical – just as are the narratives of the great movements that challenge this conservatism.

Our bodies, meanwhile, are repositories of unconscious material memory. Their genetic component (without going down the route of the collective unconscious) means that a proportion of that memory exists from before the actual creation of that body. Societies too are repositories of collective memory. The habits and instincts of persons are easy to transfer from one community to another (certainly under conditions of modernisation) but also respond (without further self-questioning thought) to the ‘norms’ of a particular time and place which then impact on the formation of memory and so identity. Memory is constructed out of continuous socialisation and the relationship between memory and social identity is at the heart of 'tradition'.

To challenge one’s own personal identity may often involve challenging one’s own body image and capabilities, the ‘norms’ of society and the representation of oneself in society – it might even suggest radical action: gender change, migration, abandonment of tribe or faith (or acquisition of one). The point is that knowing that one’s personal identity as a construct of false memory does not necessarily predispose someone to radical rather than conservative actions.

It enables radical choice, that is true, but radical choices, if based on unconscious reaction to the tension between society and material circumstances and ‘true will’ can be far from conscious. They may derive from a reaction to memory that makes them no more authentic than those of the conservative mind set who determines on full acceptance of his or her condition without further thought. Awareness that memory and so identity can be explored and reconfigured is a-political and even a-social.

The only virtue of awareness is that it does not rely on an unconscious balancing of mind, body and society (which clearly creates contentment for some but not others) but recognises that, where the mind is not in accord with body or society and where personal identity is not in line with something approaching ‘true will’, the person, in that moment of recognition, can make choices and that those choices involve the management of perceptions and the investigation of memory (or the abandonment of acceptance of memories as valid in the rejection of beliefs) in order to realign a person and the conditions of their existence.

In the case of beliefs, memory is certainly slippery. To believe something is a core element in personal identity and the shift of a belief from a present state to a memory of what was once believed represents a major shift of identity in itself. Chaos Magicians exploit this in order to play with their own identities in a way that strikes the vast majority of humanity as wasteful and absurd but these are not idle thought experiments in coming to a view on the stability of identity in our species.

So Locke is, of course, correct that our identity does rely on memory but we must recognise now that memory is constructed and false more often than not so that our personal identities are as much constructs of our bodies and society as of our conscious will and actual experience. Although this is true, this is not an excuse for a valuation of some minds as better than others just because of their awareness of this falseness of identity because no identity can ever be anything but false in an absolute sense. Nor can we necessarily draw the extreme conclusion that we have no selves (which is an entirely different argument, if currently fashionable one, to criticise another day).

Having an identity that is true to itself is still having an identity that is constructed or that has been constructed out of perceptions that can never tell the whole story about external reality (not to mention our ignorance of other minds and the workings of a society where so little can be observed directly by the subject). An identity expresses the needs at any one time of a person who is made up of a mind set in a body constrained by social and technological reality. Thus, there is never any absolute freedom but nor is there any requirement for total determination of circumstances.

Liberation is merely a cast of mind, a calibration of society, body and mind and so a calibration of perception, of memory and of identity. The constant struggle between the psychological and physical continuity theories of identity thus rather misses the point. What might be better considered is a theory of constant discontinuities in which a body (and a society) and a mind with only apparent continuity are both required but in which the ‘normal’ integration of the two can be discontinued without either mind or body ceasing to have some ‘memory’ of itself.

A body without a mind is still the body of the person and can be reactivated as such under certain conditions (as after a coma) and that body would influence a new mind that entered it through its biology and brain structure. Perceptions and capabilities would change identity – we only have to consider the male/female difference and the effects on a mind with memories of another gender in a body swap to know how identity would adjust with biology. Continuity perhaps but also a recasting of memory to fit biology would be likely.

A mind might be reloaded or transferred or duplicated in a machine or another body but, from that point, the new material conditions would create new ways of perceiving and thought that would create a separate identity from any identical mental clone in another body, whilst still showing continuities with the past through inherited shared memory. In the memory clone case, each ‘person’ has a separate identity based on possibly small changes in material circumstance despite shared memories – reproducing the ‘I’m Sharon but a different Sharon’ problem of Battlestar Galactica.

Identity is not fixed but changes and shifts in relation to the environment. It is fraught with discontinuities even when simplified down to one mind in one body. The recognition of this complexity should make the psychological-physical debate redundant. It should also help us to be suspicious of the truth-claims made about ourselves by ourselves and by all other persons of themselves and create a scepticism about claims that any single mind can have the answer to any social problem without the help of other minds or that any person can have the ultimate solution, if there is one, to one’s own problems except oneself.

Monday 16 February 2015

Ch'i

We might want to use a Chinese term to describe what is not normally

accepted as 'real' in Western culture only because it cannot be quantified.

But we do not have to accept all aspects of the Chinese term as it would

be expressed in Chinese culture. It is just that this alien word (to

Westerners) may be the best that we have to hand. I

use Ch'i rather than Qi deliberately. Qi is the genuine Chinese article

whereas I have appropriated the word Ch'i for Western use precisely because it has

been rejected in China.

This is not the same thing as, say, the Way of Wyrd. Wyrd is more implicitly directed by the Fates or Norns or Odin or some active force in Nature (as you would expect amongst Westerners) whereas the Dao, of which Qi is a manifestation, is a flow without direction, just a constant balancing of opposites. My Ch'i (as opposed to Wyrd or Qi) is not dissimilar from Orgone, another more modern variant on the theme, and is a monist materialist concept. In the end, you either sense it in yourself or you don't and, if you don't, so be it.

This is not to assume a Western vitalism. There is no reason to suppose that Ch'i does not have a material base albeit one that might change our perception of matter. Nor does it necessarily arise outside of ourselves or be connected to the world as a force that is greater than ourselves. It is probable (we think certain) that there are many individuals with Ch'i rather than a great Ch'i in which all individuals participate. The Ch'i gives out an illusory image of the universal (a theme of our Tantra series) because, since Ch'i exists here and there, evolved materially within us as individuals as our life force, then that Ch'i and this Ch'i (it is believed) must be connected so that evolution itself and the world possess Ch'i. There is no necessity in this 'leap of faith'.

This fallacy is an attractive alternative to God but it is not just that it cannot be evidenced (neither can God) but, as we say, it is not necessary. All the Ch'i we need is obtainable within us and in the relationship of ourselves to our environment and those closest to us. High emotion is Ch'i. Detachment is Ch'i. Desire is Ch'i. Withdrawal is Ch'i. The myth of universalism may be socially useful and comforting but not only is it not necessarily true but it threatens to overwhem the life force within us, our own Ch'i, by immersing it in nature or in the 'divine' or in the social as a form of loss of self that is little more than death before its time. To kill the integrated mind-body 'ego' is to kill the person without benefit other than a lifting of current and often creative anxieties.

Ch'i is an individual's vital energy, necessary for action, managed by a well-integrated will. The Ch'i of an individual can be degraded by negative external forces (including the death instinct) - by poor environment and the actions of others above all but also through a failure of will. Thus we do not have to become essentialist or animist in presuming some universal Ch'i at all. We can see Ch'i developing in us and our predecessors throughout the evolutionary process - on a path where we, humans, may be the terminus or mere staging post to something trans-human with even more energy than we have. We may want to assume that part of our individual mission is to enhance the Ch'i of others.

The cultivation of one's own Ch'i is a life's work. There is wisdom in seeing it as malleable to one's state in time, an elderly and mature Ch'i is different in quality, though not more valued, than a young and vibrant Ch'i. The old seek the vibrancy of the young but the young trade this for the experience of the mature. Ch'i also spreads out from the individual or it can be drawn in. Its influence is its glamour or its charisma. Its expressions are imagination and desire as well as brute power. It is moral not because it is required to be moral by the universal or the social but because it becomes absurd to be cruel and greedy. Bankers, bureaucrats and lawyers rarely have good Ch'i but it is not impossible that they might.

The body has a Ch'i that is both mental and physical. Good health represents the balance and flow between the mental and the physical. If you are ill and it is not absolutely organic, something is blocking your Ch'i or you are out of balance and have insufficient Ch'i or your Ch'i is being exhausted by external forces. Only you can know what you require - including outside help. Medicine here is the search for that which externally can restore Ch'i and internally restore balance. In this sense, we have much to learn from radical Western and from Eastern cultures evemn if we would be fools to abandon modern science when it comes to organic crises and failures. Ch'i may be physical or mental in its aspects but in its totality it cannot be divorced from the body or be operative without a mind.

There is no shame in categorising Ch'i medicine as 'placebo' or as complementary to more obviously materialist organic and psychotherapeutic methods. Ch'i is a third pre-emptive base line of health alongside those lines requiring organic and psychotherapeutic expertise. Ch'i is also a benign environmental solipsism. The world's aesthetic beauty and calm becomes an extension of oneself and returns to heal the inner self, adding force to Ch'i. Good Ch'i affects desire for the world, moderating it to what is most central to the person and enables a measured acquisition of goods - not only health but wealth, energy and luck.

A person aware of their own Ch'i constructs a safe and secure environment for itself without body armour against others or indulging its own fears and anxieties by choosing the death-options of religion, addiction or intellectualism. A Feng Shui mentality is not magic but an alignment of the perceiving mind with environmental reality. A Feng Shui of society does the same task by placing all persons in alignment with their Ch'i. There is no English word for this thing, this being-in-relation-to-the-world which cannot be reduced to matter in our understanding yet is ultimately part of the material base of an integrated mind-body. It is beyond science but also greater than spirit or mind. It is the existing of ourselves.

This is not the same thing as, say, the Way of Wyrd. Wyrd is more implicitly directed by the Fates or Norns or Odin or some active force in Nature (as you would expect amongst Westerners) whereas the Dao, of which Qi is a manifestation, is a flow without direction, just a constant balancing of opposites. My Ch'i (as opposed to Wyrd or Qi) is not dissimilar from Orgone, another more modern variant on the theme, and is a monist materialist concept. In the end, you either sense it in yourself or you don't and, if you don't, so be it.

This is not to assume a Western vitalism. There is no reason to suppose that Ch'i does not have a material base albeit one that might change our perception of matter. Nor does it necessarily arise outside of ourselves or be connected to the world as a force that is greater than ourselves. It is probable (we think certain) that there are many individuals with Ch'i rather than a great Ch'i in which all individuals participate. The Ch'i gives out an illusory image of the universal (a theme of our Tantra series) because, since Ch'i exists here and there, evolved materially within us as individuals as our life force, then that Ch'i and this Ch'i (it is believed) must be connected so that evolution itself and the world possess Ch'i. There is no necessity in this 'leap of faith'.

This fallacy is an attractive alternative to God but it is not just that it cannot be evidenced (neither can God) but, as we say, it is not necessary. All the Ch'i we need is obtainable within us and in the relationship of ourselves to our environment and those closest to us. High emotion is Ch'i. Detachment is Ch'i. Desire is Ch'i. Withdrawal is Ch'i. The myth of universalism may be socially useful and comforting but not only is it not necessarily true but it threatens to overwhem the life force within us, our own Ch'i, by immersing it in nature or in the 'divine' or in the social as a form of loss of self that is little more than death before its time. To kill the integrated mind-body 'ego' is to kill the person without benefit other than a lifting of current and often creative anxieties.

Ch'i is an individual's vital energy, necessary for action, managed by a well-integrated will. The Ch'i of an individual can be degraded by negative external forces (including the death instinct) - by poor environment and the actions of others above all but also through a failure of will. Thus we do not have to become essentialist or animist in presuming some universal Ch'i at all. We can see Ch'i developing in us and our predecessors throughout the evolutionary process - on a path where we, humans, may be the terminus or mere staging post to something trans-human with even more energy than we have. We may want to assume that part of our individual mission is to enhance the Ch'i of others.

The cultivation of one's own Ch'i is a life's work. There is wisdom in seeing it as malleable to one's state in time, an elderly and mature Ch'i is different in quality, though not more valued, than a young and vibrant Ch'i. The old seek the vibrancy of the young but the young trade this for the experience of the mature. Ch'i also spreads out from the individual or it can be drawn in. Its influence is its glamour or its charisma. Its expressions are imagination and desire as well as brute power. It is moral not because it is required to be moral by the universal or the social but because it becomes absurd to be cruel and greedy. Bankers, bureaucrats and lawyers rarely have good Ch'i but it is not impossible that they might.

The body has a Ch'i that is both mental and physical. Good health represents the balance and flow between the mental and the physical. If you are ill and it is not absolutely organic, something is blocking your Ch'i or you are out of balance and have insufficient Ch'i or your Ch'i is being exhausted by external forces. Only you can know what you require - including outside help. Medicine here is the search for that which externally can restore Ch'i and internally restore balance. In this sense, we have much to learn from radical Western and from Eastern cultures evemn if we would be fools to abandon modern science when it comes to organic crises and failures. Ch'i may be physical or mental in its aspects but in its totality it cannot be divorced from the body or be operative without a mind.

There is no shame in categorising Ch'i medicine as 'placebo' or as complementary to more obviously materialist organic and psychotherapeutic methods. Ch'i is a third pre-emptive base line of health alongside those lines requiring organic and psychotherapeutic expertise. Ch'i is also a benign environmental solipsism. The world's aesthetic beauty and calm becomes an extension of oneself and returns to heal the inner self, adding force to Ch'i. Good Ch'i affects desire for the world, moderating it to what is most central to the person and enables a measured acquisition of goods - not only health but wealth, energy and luck.

A person aware of their own Ch'i constructs a safe and secure environment for itself without body armour against others or indulging its own fears and anxieties by choosing the death-options of religion, addiction or intellectualism. A Feng Shui mentality is not magic but an alignment of the perceiving mind with environmental reality. A Feng Shui of society does the same task by placing all persons in alignment with their Ch'i. There is no English word for this thing, this being-in-relation-to-the-world which cannot be reduced to matter in our understanding yet is ultimately part of the material base of an integrated mind-body. It is beyond science but also greater than spirit or mind. It is the existing of ourselves.

Labels:

Body,

Body-Mind,

Ch'i,

Feng Sui,

Flow,

Health,

Materialism,

Mind,

Orgone,

Qi,

Vitalism,

Wyrd

Saturday 6 December 2014

On Madness & Socialisation ...

Are minds today different from minds in the past and why? An equally interesting question is why do some minds seem to reflect entirely the values and attitudes of the past and others to arrive at entirely new values, some of which seem to have no obvious past equivalent? How is the 'now' constructed? I am not going to try to deal with these questions here but only to pursue a train of thought circling the position of radical scepticism about what we can know about past minds.

One major problem is, of course, that we cannot know other minds even when they are present to us. This is that central issue raised by Thomas Nagel of what it is like to be a bat. We cannot really know what it is to be a bat. We are constantly imagining what it might like to be another human just as we can imagine that we know what it would be like to behave like a bat yet we cannot ever be a bat. Other humans are, in this sense, bats. We cannot be other humans. We can only surmise the contents of other people's minds from our own mind's operations and their behaviour as seen through the lens of our own experience. We rely on evidence and if the evidence is flawed, our analysis must be flawed.

Language (texts in particular) are false friends in telling us what other minds are like. Those people who say that they know that people in the past thought in such-and-such a way are really only telling us what they think other people may have thought (a 'best and most probable guess'), generally based on these false friends (as texts) which say only what a few people said in specific literary contexts or as reported by people seeking to use the words as weapons or tools for their own purposes. Even very recently, we may have archives of papers and they may tell us a great deal about how decisions were made, the tensions between people and what people said they believed but they can never give us access to the private conversations, silences and thoughts of people who may have been playing very different games from the ones outlined in those texts.

Past minds are thus largely unknown except in defined historical conditions where the minds are really just functions of a social operation and what we do know is often based on merely textual material that the past has used for its own purposes with the inner motives often masked. All texts are performances where we do not know or perhaps care what the actor is really like but only what he or she is trying to present themselves as on stage. We reinterpret the play, guided by the script and the skill of the actors, in order to present them to ourselves as what we paid to see - as exemplars, as warnings, as tales, as imaginings, as the building blocks to an argument in our local context.

However, there do seem to be differences in minds between generations that can be observed by us in the here and now and we should not assume that such differences did not exist in the past. Things do change even if we are unsure of what we can know. For example, there seem to be functional 'brain differences' emerging between minds that depend for their meaning on texts and the rest of the population and between minds that rely on printed texts and those that rely on internet 'textuality'. There is no reason why these effects of technological change should not apply as much to the past as the present. The technological conditions of each age appear to dictate not merely the forms of thought but also our ability to contextualise and judge content so the current age of high complexity and mass interactive communications suggests that the past is going to be mentally different from the present even if we cannot know much about the minds of the present and less about the minds of the past.

The shift of minds from printed texts, cinematic story-telling and still photography and art works to fast-moving video game play, internet grazing and interactivity does seem to be, literally, changing minds. Most of this is represented in the media by standard issue cultural hysteria but the issues raised are serious and they may take some time to work their way through to changes in our own capacity and culture.

Memory effects seem to be of most interest under conditions where there is no now requirement for memory palaces and loss of interest in rote learning for anything but basic skills. However, the mind that thinks in terms of textual 'canons' (where part of the personality has been pre-templated from 'great works') is very different from the mind that operates synchronically with a fast-moving world in a constant revision of mental drafts. Rote learning is also associated with traditionalist text-based canons for a good reason - both are emergent properties of the Iron Age yet we are now in the Silicon Age where general information is broadly free and widespread and not held tight by small elites. There is no point in 'valuating' this as good or bad, worse or better, but there is equally no point in resisting the facts of the matter - minds are changing and must have changed in similar ways in the past. If we have problems understanding these changes today, how can we possibly believe we know how minds functioned even in the recent past.

There are many thinkers who have prepared the ground for the new ways of thinking based on new technologies - we have often pointed out the role of the existentialists and phenomenologists and, more recently, radical trans-humanist thought - but there are also contributions from psychologists. Again, the tentative findings of consciousness studies, neuroscience and the cognitive sciences seem to be lock-stepping with our use of the new technologies. We have already noted the flawed but dynamic reasoning of Wilhelm Reich and the absurdity of behaviourism except as a functional tool but another fruitful line of enquiry is that of Lacan.

Lacan is a problem in many respects but one stands out. It is the problem of all thinkers working within a pre-ordained theory. The truth becomes impenetrable because the thinker is operative within a framework which is mere mysticism at root. Lacan's mystical belief system is Freudianism - much as others operate within Marxist or scholastic frameworks. Early Reichian theory - for example - is hobbled by Reich's commitment to Marxism. It might be argued that Lacan cannot be removed from his framework any more than, say, Lenin or Aquinas from theirs. There is some truth in this but only if we insist on treating these thinkers as texts and not as door-openers, introducers of new ideas that help drive culture even as the texts begin to ossify their followers. One should follow the ideas through to new ideas and not dwell amidst the textual interpreters of ideas.

Lacan was imaginatively engaged in the mind and was closely associated with the surrealist movement which was a living cultural force in the interwar period. It was not just that surrealism responded to a psychological theory (Freudian) but that Lacan's thought and surrealism engaged in a direct dialectic with the intellectual life of artists and thinkers.

The first Lacanian case (amongst scarcely any published) is that of Marguerite. Forget the detail (which involves a 'mad' attempt to murder a famous actress of the day) except to note that we have a paranoiac who identifies with the actress, in herself a 'false front' for social performance. Forget also that Lacan stank as a psychotherapist and was a consummate narcissist on his own account (in the minds of some, a brilliant high functioning sociopath) and see him as an interpreter of culture which is where he may have something to say to us. The desire to be an actor or actress is not uncommon but it is madness to seek to kill one because you have over-identified with her (if we accept Lacan's interpretation).

What is important here is not the case but the use to which Lacan put it. Here were the seeds of the uncovering of something that divides the contemporary mind and those who just 'exist' in inherited versions of the past - an understanding of how our identities are constructed by our appropriation of the social (of objects and of others, both real and imagined). This awareness is revolutionary and certainly derives from the 'uncovering' of the unconscious as a central cultural concept. Once we know this, then the search for individual identity or individuation (to leap across to the world of Jung) requires a shift from having the social thrust upon us in order to create our identity from without to re-ordering the social in order to have it reflect an identity that we have created for ourselves alongside the social.

What is interesting about this is that cases like Marguerite are 'mad' only because they have taken a step towards liberation (the attempt to construct an identity that chooses what to appropriate in the social to meet psychic needs) but have imaginatively detached themselves from the functional reality of the social. One is reminded of the 'mad' Last King of the Imperial Dynasty of America in Chambers' the Repairer of Reputations: the hero has a collection of books on Napoleon, the quintessential mad appropriation of the nineteenth century, on his mantelpiece. It could be argued that the fully socialised who are mere reflections of social order and have 'no individual mind' represent one radical category, the individuated who can see the social as just a set of tools for individuation as another radical category and the 'mad' (especially the paranoiac) as representing a half world radical category between the two. The 'mad' simply seek to appropriate the social (in Marguerite's case, the adulation and status of the actress) as a tool without understanding how it all works.

From this perspective, 'madness' (and an awful lot of persons are mad by this definition) is a perceptual problem about the social and its functional reality equivalent to the perceptual problems of inadequate sensory inputs but it is one that is essentially a failure of reason (as madness is classically understood) combined with a failure to 'know thyself' in a socialised context. Madness' thus lies somewhere between the rationality of the social and the reasoning of the individual - the first operating as a blind machine underpinned by manipulative social engineers (the 'reasonable' basis for individual paranoia) and the second struggling to assert the individual will against the enormity of the first (whilst not descending or ascending to the status of high functioning sociopath).

Some cannot cope with the strain - if a mind is not intellectually able to understand the machinery of the social and yet desperately seeks to be something that is not represented solely by the identity thrust on it by the social, then paranoia and other forms of mental disturbance become understandable, ranging, in the paranoid case, from the rigid conspiracy theory of the half-socialised to complete break-down. Lacan is most interested in what he thinks of as narcissism (perhaps because he identifies with it deep down) but there is a fine line here between the narcissism of the maladapted and the sensible narcissism of non-sociopathic self development on the one hand and the need to collaborate and co-operate in a complex society and the loss of self in total socialisation on the other.

And how does this fit with our introductory comments about knowing other minds in the past? Only that, when trying to understand how other past minds might have thought, the relationship between the complexity of the social and the individual and the amount of self awareness permitted in analysing the social in order to assert the individual claim against the social become relevant. To say that minds were like ours in the past is both probably true and probably false (though unknowable). Probably true is that the basic substrate of the mind is biologically similar (for simple evolutionary reasons) across vast tracts of time and probably false because that substrate is dealing with its own dialectical relationship with exponentially increasing social complexity and increasing awareness, through communications, of not only the fact of the complexity but the contingency of the complexity. Existential anxiety is thus not only a matter of death (as we have from the classical existentialists) but of the problem of social complexity and the death of social stability - of uncertainty in the relationship between the individual and the world.

Of course, while there is still room for madness today, there is less room for attributing madness simply to not being adequately socialised. So, for example, being homosexual is no longer seen as a deviation (from a norm), someone who hears voice is no longer automatically seen as insane and someone is no longer requiring treatment for saying they are a woman trapped in a man's body. Attitudes to these things represent material differences in 'what it is like to be a human being' and until we know what people in the past actually thought of such things at the micro-level of 'ordinary people' who did not write texts and did not use texts in elite contexts, we simply have to start admitting that we really do not know how past minds worked. We scarcely know how our own minds work.

One major problem is, of course, that we cannot know other minds even when they are present to us. This is that central issue raised by Thomas Nagel of what it is like to be a bat. We cannot really know what it is to be a bat. We are constantly imagining what it might like to be another human just as we can imagine that we know what it would be like to behave like a bat yet we cannot ever be a bat. Other humans are, in this sense, bats. We cannot be other humans. We can only surmise the contents of other people's minds from our own mind's operations and their behaviour as seen through the lens of our own experience. We rely on evidence and if the evidence is flawed, our analysis must be flawed.

Language (texts in particular) are false friends in telling us what other minds are like. Those people who say that they know that people in the past thought in such-and-such a way are really only telling us what they think other people may have thought (a 'best and most probable guess'), generally based on these false friends (as texts) which say only what a few people said in specific literary contexts or as reported by people seeking to use the words as weapons or tools for their own purposes. Even very recently, we may have archives of papers and they may tell us a great deal about how decisions were made, the tensions between people and what people said they believed but they can never give us access to the private conversations, silences and thoughts of people who may have been playing very different games from the ones outlined in those texts.

Past minds are thus largely unknown except in defined historical conditions where the minds are really just functions of a social operation and what we do know is often based on merely textual material that the past has used for its own purposes with the inner motives often masked. All texts are performances where we do not know or perhaps care what the actor is really like but only what he or she is trying to present themselves as on stage. We reinterpret the play, guided by the script and the skill of the actors, in order to present them to ourselves as what we paid to see - as exemplars, as warnings, as tales, as imaginings, as the building blocks to an argument in our local context.

However, there do seem to be differences in minds between generations that can be observed by us in the here and now and we should not assume that such differences did not exist in the past. Things do change even if we are unsure of what we can know. For example, there seem to be functional 'brain differences' emerging between minds that depend for their meaning on texts and the rest of the population and between minds that rely on printed texts and those that rely on internet 'textuality'. There is no reason why these effects of technological change should not apply as much to the past as the present. The technological conditions of each age appear to dictate not merely the forms of thought but also our ability to contextualise and judge content so the current age of high complexity and mass interactive communications suggests that the past is going to be mentally different from the present even if we cannot know much about the minds of the present and less about the minds of the past.

The shift of minds from printed texts, cinematic story-telling and still photography and art works to fast-moving video game play, internet grazing and interactivity does seem to be, literally, changing minds. Most of this is represented in the media by standard issue cultural hysteria but the issues raised are serious and they may take some time to work their way through to changes in our own capacity and culture.

Memory effects seem to be of most interest under conditions where there is no now requirement for memory palaces and loss of interest in rote learning for anything but basic skills. However, the mind that thinks in terms of textual 'canons' (where part of the personality has been pre-templated from 'great works') is very different from the mind that operates synchronically with a fast-moving world in a constant revision of mental drafts. Rote learning is also associated with traditionalist text-based canons for a good reason - both are emergent properties of the Iron Age yet we are now in the Silicon Age where general information is broadly free and widespread and not held tight by small elites. There is no point in 'valuating' this as good or bad, worse or better, but there is equally no point in resisting the facts of the matter - minds are changing and must have changed in similar ways in the past. If we have problems understanding these changes today, how can we possibly believe we know how minds functioned even in the recent past.